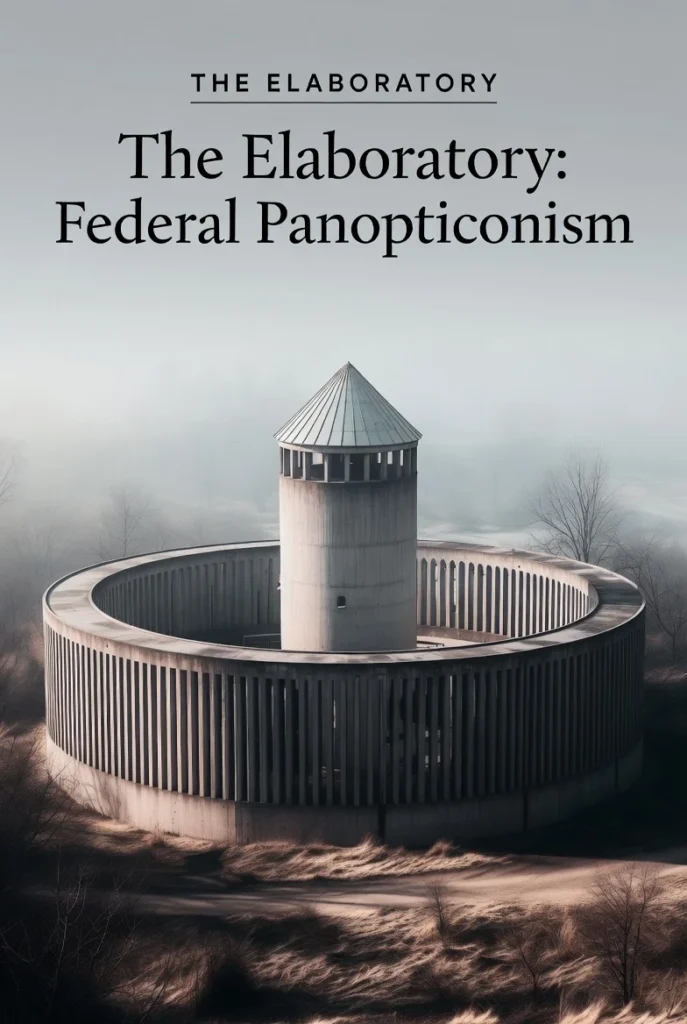

Federal Panopticonism names the convergence of state surveillance, regulatory capture, and corporate consolidation into a unified architecture of administrative control—one that renders the classical notion of “free enterprise” largely obsolete. It describes not a conspiracy or a sudden rupture, but a structural transformation in how power is exercised and how legitimacy is granted within contemporary political economy. We may call it the Elabratory.

Unlike earlier forms of centralized authority, the Elabratory does not rely primarily on overt coercion or explicit prohibition. Its power operates through continuous visibility, procedural dependence, and managed access. Economic and communicative participation is permitted only insofar as it conforms to an increasingly dense lattice of institutional permissions. What was once framed as the “Land of Opportunity” has been replaced by a panopticon of controlled entry, where legitimacy is conditional and revocable rather than presumed.

The metaphor is intentional. Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, later generalized by Michel Foucault, described a system in which constant visibility induces self-regulation without the need for direct force. Individuals internalize surveillance and adjust their behavior accordingly, even when no observer is visibly present. The Elabratory extends this logic far beyond prisons or factories into the total administrative environment of modern life. Visibility is no longer confined to physical space but embedded in financial records, compliance databases, platform analytics, and algorithmic risk assessments.

This system is not the organic outcome of free exchange or decentralized competition. The Elabratory is actively sustained by policy choices that favor scale, incumbency, and financial abstraction over productive plurality. Decades of near-zero interest rate monetary policy have disproportionately benefited asset holders and large institutional borrowers, while eroding the viability of small, capital-constrained enterprises. Corporate bailouts and targeted subsidies have further entrenched market concentration by socializing losses while privatizing gains. Meanwhile, regulatory frameworks have grown not merely in scope but in complexity, functioning less as neutral safeguards than as structural barriers to entry that only large organizations can afford to navigate.

Empirical research consistently shows that regulatory burden scales regressively. Compliance costs fall most heavily on new and small firms, while incumbents absorb them as a fixed cost of dominance. George Stigler’s theory of regulatory capture explains how this outcome is not accidental: regulatory agencies, over time, come to serve the industries they oversee rather than the public interest they were designed to protect. The result is a political economy in which competition is formally celebrated but structurally suppressed.

Within this context, the role of the financial system has undergone a fundamental shift. Rather than primarily facilitating productive commerce, it increasingly serves to move, obscure, and leverage vast flows of capital. Shell corporations, offshore jurisdictions, and complex derivative instruments enable wealth to circulate independently of real economic output. Asset prices inflate through monetary expansion rather than productivity gains, distorting price signals and decoupling capital allocation from underlying value creation. This process, widely described as financialization, has been extensively documented across advanced economies since the late twentieth century and has concentrated wealth and decision-making power in a narrow financial and managerial elite.

Legitimacy under Federal Panopticonism is no longer a default condition of participation but an administrative achievement. To operate “legitimately” requires continuous negotiation with overlapping regimes of Elabratory permission: licenses, certifications, tax codes, reporting standards, banking compliance requirements, payment processor rules, and platform governance systems that determine visibility and reach. Participation becomes conditional, provisional, and continuously audited. Operating outside these structures is not merely riskier; it is isolating. De-platforming, denial of banking services, or regulatory enforcement, a segregation labelled ‘epartheid,’ can exclude individuals or organizations from economic and communicative life without the necessity of formal criminal adjudication. As a result, the distinction between lawful and unlawful activity collapses into a more ambiguous division between sanctioned and unsanctioned existence.

Artificial intelligence (AI) does not originate this system, but it is its most effective instrument. AI systems do not reason, deliberate, or exercise moral judgment. AI strength lies in pattern recognition, probabilistic inference, risk scoring, and behavioral prediction. These capabilities align precisely with the needs of large-scale administrative governance. AI enables preemptive classification, sorting populations into categories of acceptability, risk, or deviation before any overt transgression occurs. “We know what you are feeling.“

In this role, AI functions as an amplifier of compliance and a mechanism of normalization. Rather than engaging subjects as agents, it diagnoses them as data profiles. Decisions are rendered opaque, automated, and difficult to contest. In this sense, AI constructs isolation chambers: environments in which individuals are economically and communicatively enclosed, continuously evaluated, and subtly nudged toward conformity through incentives, restrictions, and visibility modulation.

Paradoxically, the only exits offered from these isolation chambers are echo chambers and their attached outrage casinos. Algorithmic systems reward conformity within bounded ideological, behavioral, or commercial lanes while penalizing cross-boundary discourse. What emerges is not pluralism but managed fragmentation and recursion into an angry mob on behest of the echo chamber pod boss. Populations are segmented into predictable, non-interacting clusters whose internal dynamics can be modeled, monetized, and controlled. This fragmentation is not an unintended side effect; it reduces collective agency while preserving the appearance of choice and diversity.

The isolation produced by Federal Panopticonism is therefore not merely social or psychological. It is economic, communicative, and structural. It operates automatically, without the need for centralized intent, through systems that reward transparency upward and opacity downward, compliance over experimentation, and scale over independence. The system is not simply tilted; it is sealed.

What remains is a closed terrarium. Participants are told they are free to grow, innovate, and compete, while the essential conditions for independent growth—neutral capital access, unmediated communication, and institutional symmetry—are systematically withheld. In such an environment, freedom persists as rhetoric, not as structure. What remains is not a market, but an administered environment: The Elabratory.

References

Bentham, J. Panopticon; or, The Inspection-House. 1791.

Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage Books, 1977.

Stigler, G. J. “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, vol. 2, no. 1, 1971.

Philippon, T. The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets. Harvard University Press, 2019.

Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs, 2019.

Krippner, G. Capitalizing on Crisis: The Political Origins of the Rise of Finance. Harvard University Press, 2011.

Bank for International Settlements. Annual Economic Reports, multiple years.

Dal Bó, E. “Regulatory Capture: A Review.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol. 22, no. 2, 2006.

Pasquale, F. The Black Box Society. Harvard University Press, 2015.